The evil eye is an ominous, foreboding spectre that lingers in the minds of many across the globe. Many cultures claim the term, but the contexts of its existence and the symbolism created to represent it varies drastically by location, religion, and culture.

As a forewarning, the evil eye is found in many cultures around the globe; however, this particular blog will focus only on its existence within Judaism. There is a high chance that what you read here will resonate with your understanding of your culture as these beliefs are shared globally.

“The belief in the Evil Eye is found throughout the ancient cultures that came into contact with Judaism...In ancient and early medieval rabbinic Judaism, the Evil Eye was perceived as an occurence of every-day life, part of the reality that the rabbis had to deal with in their own manner of understanding and interpretation. This is the reason why it is prevalent in rabbinic texts. Through the use of the Evil Eye is explained from the point of view of magic, the means believed to be effective for protection of healing after often religious ones.” (1)

What is the Evil Eye?

The evil eye goes by many names. In Hebrew, áyin hā-ráʿ עַיִן הָרַע, while in Spanish, for example, Mal de Ojo or Mal Ojo. Whatever the name, it generally refers to the same phenomena.

Simply put, the evil eye is the belief or idea that someone can be bewitched, cursed, or harmed by being cast an evil glance or look. This look can be intentional or unintentional, as well as caused by envy, greed, jealousy, etc.

How the evil eye works varies by tradition, oftentimes directly contradicting itself.

“G‑d is the epitome of kindness. As such, Heaven does not generally judge a person in the strictest possible manner. But when one negatively gazes at another’s good fortune with ill feelings or envy, he is essentially asking, “How come that person has XYZ?” This arouses the latent harsh judgment Above, and the person is judged strictly according to what he deserves. So if there is already some sort of existing sin, the evil eye can amplify it and cause the person to be judged in a strict and unfavorable fashion.” (2)

There is often a belief that the evil eye does not exist within official Rabbinic literature, but this is incorrect. In truth, there is a great deal of debt owed to the women in Jewish communities who carried these traditions, many of which had practical applications, should one not believe in the spiritual danger of the evil eye. This requirement of rabbinic validation may stem, in part, to embedded misogyny within the culture, an unfortunate symptom of a greater problem that places the beliefs of men above those of women, directly contradicting the Jewish belief in the inherent spiritual prowess of women.

“My father knew ayin hara [evil eye] in Hebrew, while I know kozas de mujeres [things of women]” (6).

This belief that only certain people are capable of the evil eye varies and falters within Jewish tradition. In the same contradictory vein, it was often believed that it was women who were largely capable of the evil eye, as well as constantly on guard against it. It would appear that the literature flops between honoring men as capable of the most devastating evil eye and women being inherently more prone to magic and therefore more likely to use and defend against it.

But, to assuage those who require heteropatriarchal validation, the evil eye does appear within Rabbinic sources and has even shaped Jewish law.

Joshua Trachtenberg cites Rabbis within the Talmud, who were believed to have the power to turn men into “heaps of bones” with nothing more than a glance. This perception of the evil eye causing instantaneous physical harm or even death is less widespread within certain communities of Judaism. As Trachtenberg mentions, this may be due to overtly Babylonian influences.

There are numerous Midrashic mentions of the evil eye. Genesis Rabbah 45:5-6. Genesis Rabbah 53:13, Genesis Rabbah 56:11, Midrash Leviticus Rabbah 17:3, Midrash Leviticus Rabbah 26:7, Midrash Numbers Rabbah 12:4, Midrash Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:25, Midrash Numbers Rabbah 12:4, Midrash Tanchuma 66, to name a few. Further mentions include: Talmud Sanhedrin 93a, Talmud Shabbat 34a, and Talmud Bava Batra 75a, for a few more. Some take another approach, “Although the Talmud does lend a measure of credence to the evil eye, it also tells us that “one who is not troubled by it, will not be troubled by it.”11 Don’t be bothered by it, and it will not bother you.” (2)

The Nishmat Chayyim 33:27 says there are three sources for the evil eye:

-

Intense attention from others

-

Intentional harm (like a curse)

-

Jealousy of demons

As demons were believed to be “active agents in malevolent sorcery”, they were naturally involved in the casting of the evil eye–whether by themselves or on behalf of another. According to Menasseh B. Israel, demons are like men, “When a man receives praise in the presence of his enemy, the latter is filled with anger and reveals his discomfiture, for envy consumes his heart like a raging fire, and he cannot contain himself” (4).

According to Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women, it is similarly the spirits who carry out the evil intent of the evil eye—even if said evil eye is unintentional. “For instance, one's passing compliment could bring illness to a baby. It was the spirits who heard the praise and who brought illness to the little one. Why would they so willfully cause pain to an innocent? Because they, themselves, were envious of beautiful, healthy children. They were given power to act out their envy through the agency of human beings” (6).

These descriptions aside, it appears that Biblical Jews were not necessarily concerned with the mechanics of the evil eye as much as they were concerned by its impact on their lives.

Rabbi Judah Löw, the supposed creator of the famed Golem of Prague is credited with the opinion, “Know and understand that the evil eye concentrates within itself the element of fire” (4). But, his opinion is not the only one.

“The angry glance of a man’s eye calls into being an evil angel who speedily takes vengeance on the cause of his wrath” is the belief of Menasseh B. Israel. (4).

Though “[t]here is no direct proof that the Israelites were concerned about the power of the evil eye in biblical times, but no doubt they too sought means to defend themselves against all kinds of threatening evil powers. Two silver amulets found in a burial cave in Ketef Hinnom in Jerusalem attest to the apotropaic function of the blessing of the priests (Num 6:24-26) in Judah at the end of the First Temple period (ca. sixth century B.c.E.). According to the preamble to the blessing, the amulets protected their owners against "the Evil" qualified by the definite article: "May he [or she] be blessed by God, the rescuer and the rebuker of the Evil." Later, the midrash explicitly connects the apotropaic character of the priestly blessing with the evil eye: "When Israel made the Tabernacle the Holy One, blessed be He, He gave them the blessing first, in order that no evil eye might affect them. Accordingly it is written: 'The Lord bless thee and keep thee' (Num 6:24), namely, from the evil eye" (Num. Rab. 12 A; Pesiq. Rab. 5).”

It is however, both a weapon to be in defense from, but also to be weaponized in protection.

What Does the Evil Eye Do?

The evil eye is believed to cause misfortune, bad luck, illness, miscarriage, and even death.

The cause of illness may be down unwittingly someone who possesses the evil eye (4). According to the Talmud (Bava Metzia) 107b), ninety-nine out of a hundred people die of the evil eye (5).

Misfortune may impact a single person or a community, though it is noted that within Sefardic communities, it was mostly women and children who were stricken with the affliction of the evil eye (6).

There were a number of identifiers of the evil eye, aside from the obvious strings of bad luck, misfortune, illness, miscarriage, or death. For some Sefardic communities, a child yawning a lot could be interpreted as the manifestation of the evil eye (6).

“In rabbinic literature, the Evil Eye usually denotes the power of an individual to affect others adversely by merely looking at them. The Evil Eye is often seen as an expression of envy and hatred. One source contends that the Evil Eye was considered the major cause of death. It is listed as one of the seven causes of sickness or disaster.” (8)

Warding Off the Evil Eye

In a world where such evil exists, people seek to prevent and remedy it when presented with such an option. There are hundreds of methodologies, but most fit within the bounds of ma’asim (rituals), segulot (folk remedies), and kemiyiot (amulets).

Popularly, reciting Tehillim (Psalms) is believed to be a powerful protectant, as is the Shema. The practice of reciting the Shema outside of regular prayers has existed for centuries as an extra measure of protection from the evil eye and demonic activities.

Different Jewish communities developed their own variations of methodologies to protect themselves and their children… For instance, in Iraqi Jewish families, “While the mother glorifies her children, she curses their enemies who might hurt them with the evil eye. She is sure that it is her children who will hurt their enemies:

O Jacob, the doctor, son of the doctor,

Wounding the enemy in a place which will not heal.” 3

One particularly popular recitation against the evil eye is as follows:

“Then Israel sang this song: Spring up, O well- sing to it. The well which the chieftains dug, which the nobles of the people started, with maces, with their own staffs. And from Midbar to Mattanah, and from Mattanah to Nachaliel, and from Nachaliel to Bamot, and from Bamot to the valley that is in the country of Moab, at the peak of Pisgah overlooking the wasteland. (Numbers 21:17-20) (4) (5).

Further, the Priestly Blessing (Numbers: 6:24-26), is also efficacious (5).

“The Lord Bless you and keep you. The Lord make his face shine upon you and be gracious unto you. The Lord lift up his countenance toward you and grant you peace”.

The Hamsa, particularly one with the image of an eye in its center, is a particularly effective symbol (5), as are fish, “Since fish have no eyelids and thus their eyes never close, they can always ward off the evil eye; additionally, their eyes are located on both sides of their heads so they can see everything and be ever-vigilant against evil” (6).

Common actions against the evil eye include, but are not limited to:

-

Avoid double marriages within a household

-

Break glass or ceramic at a wedding

-

Never mention a date or birth or exact age

-

When taking your child to school for the first time, shield them with your cloak or coat

-

Add or begin a statement of praise with “no evil eye” or equivalent versions in other languages

-

Spitting thrice

-

Pinching the earlobes

-

When saying something negative, preface with chas v’shalom or chas v’chalila—also used as a response when hearing something negative, particularly a prediction

-

Do not use the term “evil eye” but instead “eye” or “good eye”

-

Tie a red thread or lace around the neck or wrist of a newborn

There are, of course, far more intense rituals and practices designed to ward off and remove the evil eye. These can be as simple as wax or lead casting or as complicated as a ten to fifteen step ritual requiring specific ingredients.

Many of these remedies were created and carried on by women of the communities–despite much of the modern literature crediting men for their work.

Isaac: Did you have any amulets against the evil eye?

Avram: Ah, yes, I remember it. They put it on. When I would put on new clothing, my mother would put one on me. They used to put here paper with things of women. I don't know what was inside.

Isaac: Who used to write these things? The rabbis?

Avram: Na! The women did it. It was the business of the women. No, it was not hahamim (rabbis, learned men]. They didn't occupy themselves with such things. The only thing they did to us was when we were going to put on new clothes, they would pin a little paper right here. What was inside I don't know.

Isaac: Una nuska an amulet ?

Avram: Yes, di kaza, di mujeres (of the house, of women], not from hahamim. For evil eye. (6)

Throughout Jewish communities, herbs were an effective protectant against the evil eye, in particular Rue, Garlic, Rosemary, and Cloves. Salt and saltwater were also favored for preventing or curing the evil eye.

In the Middle Ages, it was common for Jewish children to wear coral necklaces, as the color red was seen as inherently anti-demonic and anti-evil eye (4). Other amulets, written amulets not included, are blue beads (pinned to clothing, sewn into the lining, or worn as jewelry), gold (jewelry, amulets, coins, etc), horseshoes, and iron objects like nails (6).

The Amulet

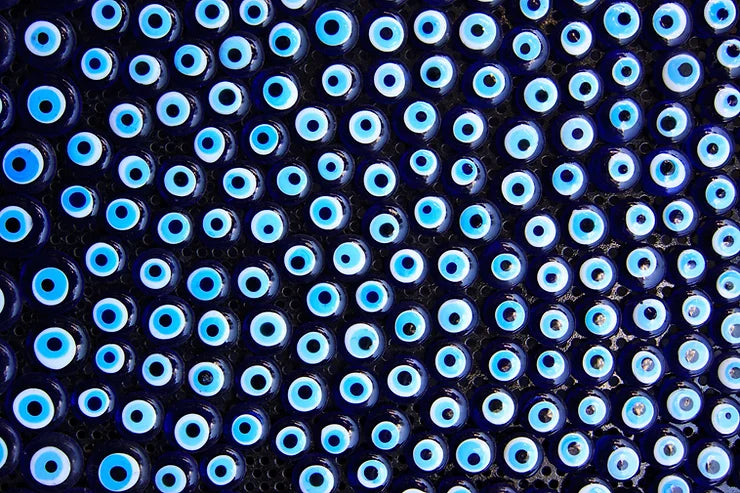

When people think of the evil eye, they generally think of the imagery of a blue eye, like this evil eye 🧿. This amulet is known as the nazar in Turkish and that name has been adopted by the masses–though there are many names for it, which vary by community–evil eye, ayin hara, μάτι mati, עַיִן הָרָע ,عين, mal de ojo, just to name a few. While it is called the evil eye, it is not harmful and does not cause the evil eye, but rather diverts it.

The color blue is most commonly utilized in these amulets, though they appear in many colors. It is believed to have originated in South West Asia & North Africa, particularly Turkey.

However, due to both cultural diffusion and colonization, the symbol has made its way across the globe.

While it can appear in any color, the color blue does hold special significance within Judaism as a protective and holy color, “Medieval kabbalistic symbolism played an important role in constructing the color blue as a powerful color; it provided blue-colored objects with the power of the godhead, thereby turning them into talismans. In Kabbalah, the godhead is described as a complex of ten manifestations or gradations called sefirot, each gradation is a distinctive aspect of the godhead, such as mercy or judgment. One of the prominent characteristics of kabbalistic language is the usage of symbols to describe every gradation and the system as a whole. These symbols are not only signifìers of the divine; every symbol is also an embodiment of the corresponding gradation, carrying some of its divine characteristics. (7)

Variations of the symbol, in both color, shape, detail, and combination with other symbols, are wildly popular around the world.

Impact

Belief in the evil eye has even shaped Jewish law, though its greatest extent is in cultural practices. Children are taught, even without knowing, ways to avoid the evil eye. Being taught to be modest, refrain from bragging, etc, is not merely for reasons of politeness. As envy and greed are large proponents of the evil eye, children are raised in a way to avoid such casualties.

Is it a Closed Practice?

Because of the wide variations of the evil eye around the world, there is no way that the umbrella term can be, in and of itself, closed. However, there are ritual practices to ward off, repel, and cure the evil eye that can be considered closed.

The amulet 🧿 is often debated in this conversation–however, due to colonization and the dispersion of various diasporas and religions from the SWANA region, the amulet can be found within cultures around the globe. One cannot tell if someone comes from a culture or religion which utilizes the amulet solely based on their physical appearance or country of origin.

The history of the symbol is deeply complex, but what we do know is that it is massively important for people of many cultures and deserves our deep respect.

Sources:

1 https://www.proquest.com/docview/200408277?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

2 https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/166909/jewish/What-Is-the-Meaning-of-the-Evil-Eye.htm

https://www-jstor-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/stable/1260090?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents 3

4 Jewish Magic and Superstition: Joshua Trachtenberg

5 Divination, Magic, and Healing: The Book of Jewish Folklore by Rabbi Ronald H. Isaacs

6 Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women

7 https://www.jstor.org/stable/44505334

8 https://www.proquest.com/docview/200408277?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true